One “tech” story that seemed to be missing from most of those decade-in-review pieces is that of the “right to be forgotten”. Although this issue is really more about privacy and use of personal data, it’s more relevant to tech than stuff like Amazon extorting local communities in their “search” for a new headquarters.

The concept first jumped on the radar for most people in 2014 when the European Court of Justice ruled that EU citizens had a right to ask search engines to remove “inadequate, irrelevant or no longer relevant” information from their results.1 I first began following this issue around that time and, as you might expect, nothing about this decision turned out to be that simple.

Things became far more complicated four years later when a much larger collection of laws and regulations (some existing, some new) regarding data control and privacy, called the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)2, came into effect in the EU. Among other things, the GDPR provided for some pretty heavy fines for companies and organizations who violated the regulations.

While that’s all happening in Europe, the question still stands: do humans have a right to be forgotten?

Back in the days before the internet and Google, it was much easier to ignore something from your past. However, if the act was newsworthy enough, the chance was good that it might reappear.

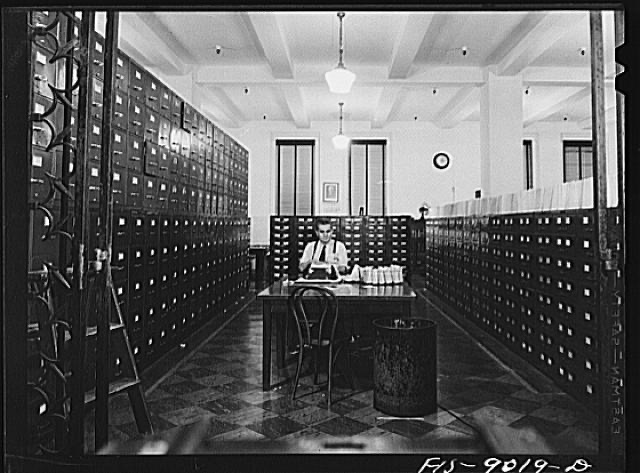

Beginning early in the 20th century, newspapers started organized collections of physical clippings from past issues known as the “morgue”. When reporters needed some background information for a current story, they went rummaging through the file cases to find something from the past that might be relevant (or sent a Jimmy Olson-type to do the dirty work).

Very little was “forgotten” in the morgue, although those bits of information that someone might find inconvenient were also not readily available to anyone but the intrepid investigator. In the age of digital information, we call those morgue files “archives”. And large chunks of information we might wish would stay buried is much easier to locate.

Today it’s not just newspapers that collect information on people and events. Just about every company, organization, and government agency sucks up every bit of data they can find on anyone and everyone. Those archives can be valuable profit centers. They’re also often too easy to misuse.

So, we come back to the original question: do you really have a right to be forgotten? And is that even possible?

I suspect the answer to the second part is, no. Implementation of the GDPR in Europe has been confusing at best, with some countries like France and India trying (unsuccessfully, so far) to extend their rules to the rest of the world.

And just this month, the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) became law in that state. The package includes some of the same provisions as the GDPR, along with bringing much of the same confusion about who and what is covered by the regulations.

Bottom line, the best answer to the title of this rant is “stay tuned”. It will be very interesting to see how all this attention now being paid to the collection and use of personal data plays out.

I suspect nothing about it will be simple.

The picture, from the Library of Congress, shows part of the morgue at the New York Times in 1942.

1. The Wikipedia page on the subject is pretty comprehensive, and growing.

2. Wired has a good summary of the GDPR, and how it impacts people not living in the EU, if you’re interested in exploring further. xkcd also offers some wonderful commentary on the GDPR in the form of an update to their terms of service, if you want a laugh.

Leave a Reply